What is Molly?

MDMA (often called ‘Molly’ or ‘ecstasy’) has become one of America’s favorite drugs since the 1980s, when it ‘escaped’ from the world of profesional MDMA therapy and became popular among partiers. Usually taken as pills or capsules, the drug typically produces an energetic high with a profound sense of peace and joy that lasts for around 3-6 hours (depending on dosage and individual.) It isn’t a true psychedelic, but it’s effects are richer and more ‘spiritual’ than those of simple stimulants like amphetamine. Since it strips away emotional defense mechanisms and encourages socialization and bonding, some scientists have dubbed the drug an “empathogen.” Among young adults (ages 19-30), about 14% have taken MDMA.

The history of MDMA

Christmas Eve, 1912: The pharmaceutical company Merck files for a patent on MDMA (‘ecstasy’) as a precursor to a drug that they hoped would be effective in controlling bleeding. Their patent application is granted two years later (1914.) In spite of persistent rumors, there is no evidence that they were aware it was psychoactive or intended to market it as a product.

1927: Merck researchers perform some animal experiments, noting that the substance had some similarities (in structure and effects) to adrenaline.

1953-1954: The US Army conducts animal experiments with MDMA and a number of structurally related drugs. What they hoped to discover is unclear, but the research was labeled as sensitive and not declassified until 1969. It seems likely they were seeking new non-lethal chemical weapons or interrogation tools.

1959: Merck researchers again investigate MDMA’s potential use as a stimulant. There are rumors that it was investigated as a drug to keep aviators alert, but no evidence of human experiments has been found.

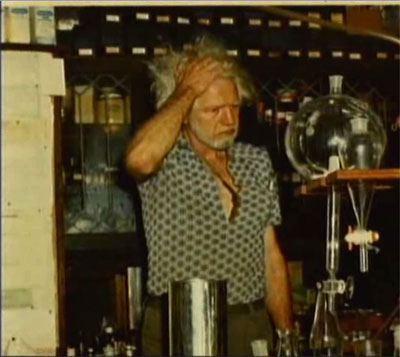

1965: Independently predicting that MDMA might be psychoactive, a chemist named Alexander Shulgin (above) synthesizes MDMA while working at Dow Chemical, but does not try the substance. Shulgin had made Dow a tidy sum of money with his prior work on a biodegradable insecticide, and as his reward was allowed to pursue whatever field of research appealed to him. Shulgin chose to study psychoactive drugs…a decision that would eventually impact the entire world.

1967: A student at the University of California/San Francisco describes having taken MDMA to Shulgin. Eventually, Shulgin tries the new drug himself…and is amazed.

1972: MDMA is seen in Chicago by police. Use is apparently slowly spreading, but it remains a rather rare drug.

1977: A friend of Shulgin’s, psychologist Leo Zeff, begins to prepare for retirement from his practice. While starting to clean out his office of memorabilia, he invites Shulgin over to see if the chemist would like any of the items. Shulgin, in turn, brings him a gift: A small vial of MDMA, and a suggestion that he might find the material worthwhile. Leo, who was experienced with psychoactive drugs and had used them in his practice for some patients, accepted the gift without committing to whether or not he might try it.

Several days later, Shulgin receives a phone call from Leo. He has tried the MDMA. He no longer wants to retire. Instead, he begins to use the new drug, first in his own practice, then introducing other therapists to it. The ability of MDMA to help patients overcome emotional barriers was so striking that one psychiatrist dubbed it “penicillin for the soul.” When Dr. Zeff passed away years later, his widow estimated that the network of therapists using MDMA had grown to about 4,000.

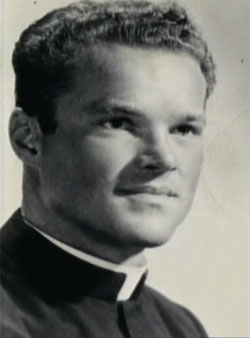

1984: All hell breaks loose. The growing networks of therapists, chemists and users, which had managed to stay largely below the radar of the government, becomes impossible to ignore when the young Michael Clegg begins openly selling MDMA in Texas, using advertising, a 1-800 number to place orders, and even offering shipping. A former seminary student, Clegg considered himself an ‘Ecstasy missionary’ (having given the drug that name himself) destined to help bring MDMA to the public. At its peak, he was delivering half a million pills a month to the Dallas area.

Responding to the crisis of people being able to get high without risking arrest, the Drug Enforcement Agency announced its intent to Emergency Schedule MDMA, placing it into Schedule 1 (the most restrictive class of drugs, such as heroin) for a year while it was decided how it should be permanently Scheduled.

Shocked and angered by the DEA’s plans to completely ban access to a drug that had become an important and valued part of their practices, psychiatrists, therapists, and other scientists and doctors challenged the Scheduling, resulting in government hearings on how MDMA should be Scheduled.

1985: The hearings began. The DEA appointed Judge Francis Young to hear the case. Months of testimony and sometimes bitter argument went by as the hearings dragged on through the summer, autumn and into winter.

1986: On May 22nd, Judge Young released his decision on the laws, science, and use surrounding MDMA, declaring that MDMA was safe when used under medical supervision, did not have a high potential for addiction, and had legitimate medical use. As such, Judge Young said, it was not legal to place MDMA higher than Schedule 3. This much less restrictive category would have allowed doctors to continue to use MDMA, but would have still made sale without a prescription illegal.

Angered by these findings, the DEA condemned Judge Young as biased, shortsighted, and incorrect in his interpretation of the laws. They rejected his non-binding ruling and declared MDMA permanently Schedule 1.

Outraged by the DEA’s attempts to re-write the laws and ignore the science, the groups that had first challenged the Scheduling of MDMA sued, taking the DEA to court.

1988: After several years of motions, hearings, and angry debate, the doctors and scientists appeared to have achieved victory: On January 27, the courts agreed with Justice Young’s original opinion and ordered the Drug Enforcement Agency to reassess its Scheduling decision. In the meanwhile, MDMA is removed from Schedule 1, becoming briefly legal once again.

The DEA, complying with the court order, ‘re-evaluated’ their decision. And decided that they had been right all along, and the doctors, scientists, and courts were the ones that were wrong about the science and the law. They permanently declared MDMA Schedule 1, taking effect on March 23, 1988.

Vindicated in their interpretation of the law, in the science and in court but beaten down by sheer political power, the doctors and scientists were defeated. The prohibitionist bureaucrats had lost every battle but won the war, and MDMA has remained in Schedule 1 since.

1991: Alexander Shulgin’s legendary book, “PIHKAL” is published, and the world discovers what ‘Sasha’ has been up to in the past few decades. (The book’s title is short for “Phenethylamines I Have Known And Loved”, a reference to the basic chemical structure he based his work on.) The book itself is divided into two parts: The autobiographies of Alexander and his wife Ann; and a massive drug section describing the structures, dosages, effects, and synthesis of nearly 180 psychoactive drugs, most of which Shulgin had invented; many of which were new to science. (The Chemistry section is available on-line.) Within the book were also glowing descriptions of the effects of MDMA:

“I feel absolutely clean inside, and there is nothing but pure euphoria. I have never felt so great, or believed this to be possible. The cleanliness, clarity, and marvelous feeling of solid inner strength continued through the rest of the day, and evening, and into the next day. I am overcome by the profundity of the experience…”

Today, most of the psychedelic drugs that have been prohibited in America were born in Shulgin’s basement laboratory, and his work continues to inspire the invention of even more new drugs.

March, 2001: Alarmed by skyrocketing use of MDMA and their own clear inability to stop it, the US government increases penalties, making the distribution of MDMA ten times more severely punished, dose for dose, than heroin. In spite of being opposed by prominent scientists and even the former head of the National Institute on Drug Abuse as irrational and a diversion of resources from the control of truly dangerous drugs, the measure passes easily.

November 2, 2001: Revenge of the Scientists. The US Food and Drug Administration gives approval for human testing of MDMA for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder to the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies. MAPS, a group made up of many of the same doctors and researchers that had originally fought tooth-and-nail to keep MDMA available to doctors, is conducting the research as part of their plan to gain full FDA approval of MDMA as a prescription drug. The next two years would prove to be a long, difficult struggle to gain IRB approval (Institutional Review Board oversight is needed to conduct human research.)

September 5, 2003: The infamous MDMA researcher George Ricaurte, who’s work had been the cornerstone of MDMA prohibition and anti-MDMA government ad campaigns, confesses: One of his most recent and sensational studies, claiming that a “common recreational dose” of MDMA could cause extensive brain damage and Parkinson’s-like symptoms never actually happened. The monkeys used in the experiment had actually been given near-lethal doses of methamphetamine; not MDMA!

September 23, 2003: With Ricaurte disgraced, the “it’ll eat holes in your brain” house of cards began to come tumbling down; MAPS was finally given approval for human research with MDMA.

April 6, 2004: The first dose of MDMA in MAPS’ post-traumatic stress disorder study is administered.

January 2017: After years of careful research, the FDA agrees that MDMA shows promise as a prescription medication and gives approval for Phase III trials; the last stage of studying a new drug before it can become available by prescription.

To support or get more information on this ongoing research, visit MAPS.org. MAPS also maintains a complete record of the Scheduling fight, including government documents, testimony and court rulings.